Long duration energy storage: state of commercialization

Long-duration energy storage (LDES) is often described as the missing piece for a fully renewable grid. But despite increasing attention and policy support, the technology is running up against market realities: cost, readiness, and competition from lithium-ion.

Long duration energy storage (eight-hour+) is supposed to be the next big unlock for renewables. But according to Sightline’s latest analysis and utilities’ real-world procurement experience, LDES is running into a harder truth: today, cost and readiness still point to short-duration lithium-ion batteries most of the time, and long-duration lithium-ion batteries when a government mandates LDES.

At a recentSightline client-only session, industryexperts drilled into the state of long-duration energy storage commercialization, and found that the technology still needs a little more charge before it can truly compete to help power the future.

TLDR:

- LDES is not yet profitable. Eight-hour systems cost too much relative to four-hour storage, even if markets compensated for the extra duration. Cost reduction, not capacity market design, is the key unlock.

- Revenue guarantees are the bridge. UK, US, and Australian procurement programs will determine which technologies survive. Only a handful of companies have the readiness to even compete in these tenders, and it is unclear if any have sufficiently low costs to win.

- Lithium-ion is setting the pace. For 8+ hour projects in the 2020s, most deployments will be lithium-ion because it is bankable and inexpensive. Lithium-ion is a mature technology that benefits from existing manugacturing scale. Plus, for procurers, there's contracting familiarity and standardization.

- Utilities want long duration storage, but only when it makes sense. Reliability needs will grow, especially in winter peaking grids with rising demand. But economics still point to four-hour systems for now.

- A narrow path forward. A small group of companies that reach demonstration, align with near-term tenders, and secure financing could still scale. Everyone else risks missing the market window.

What happened

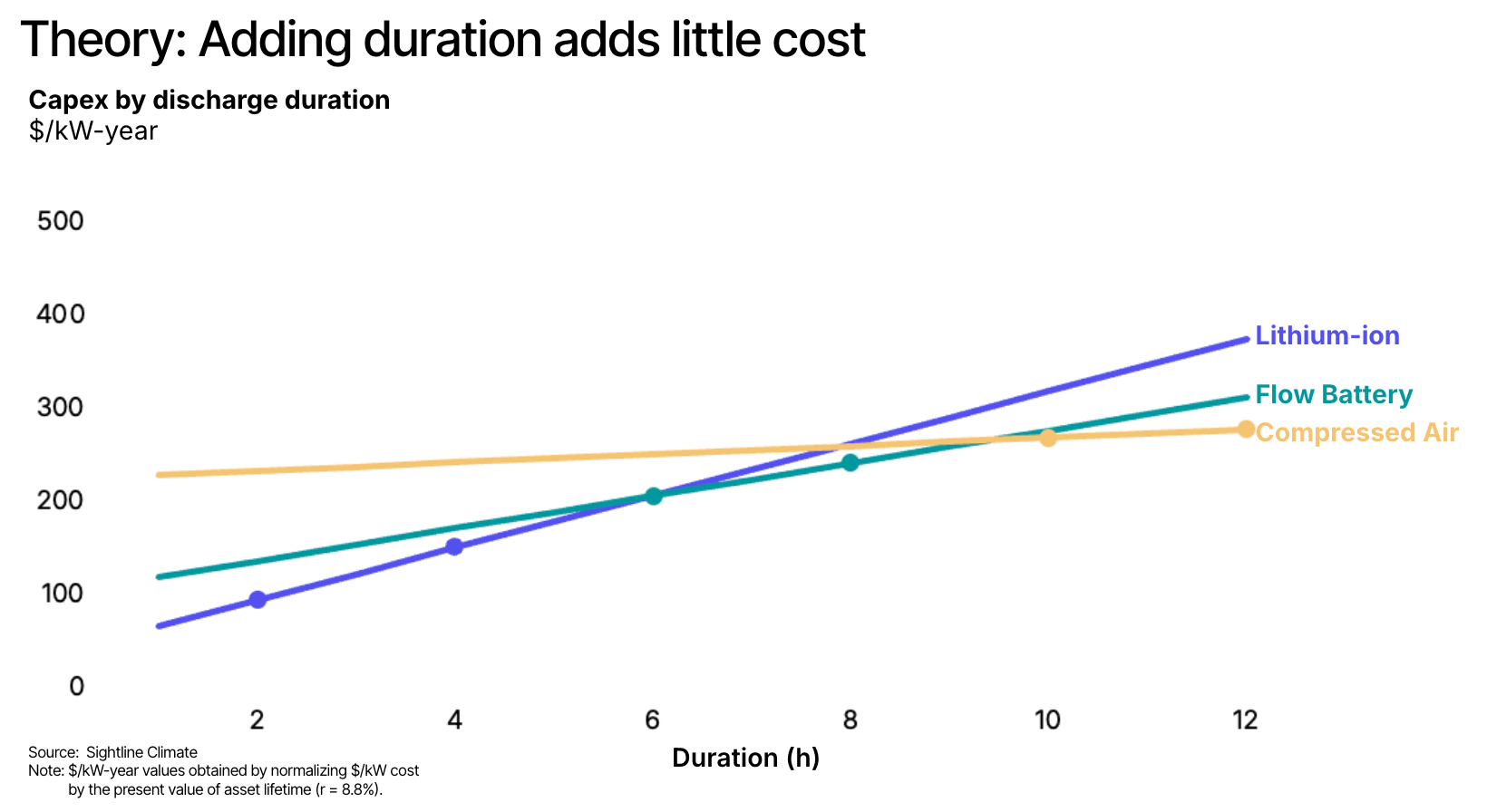

The webinar explored the core challenges and opportunities for emerging and existing LDES technologies. The core challenge: the cheapest eight-hour systems cost almost twice as much as four-hour batteries on a per kW-year basis, while emerging technologies are even more expensive.

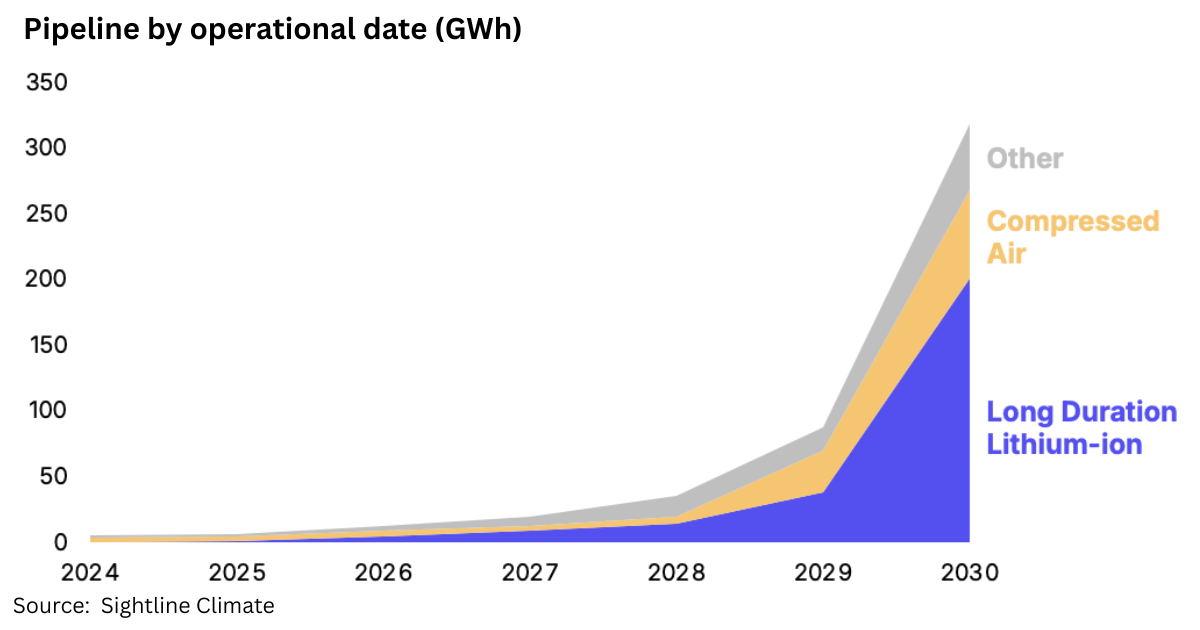

The webinar presentation argued that LDES deployment at commercial scale relies on policy support because LDES is not profitable on a level playing field with short-duration storage. In part because market rules do not fully value LDES, but more importantly because LDES is too expensive. And despite heavy interest in new technologies, long-duration lithium-ion makes up the majority of the 2030 project pipeline.

Why it matters

LDES sits at the center of the clean firm power debate. Inter-day (8-12 hour) storage could help grid operators manage winter peaks, reduce renewables curtailment, and support rising load from data centers. But emerging technologies are underperforming compared to the dizzying pace of innovation in the lithium-ion industry, preventing cost parity with the incumbent, let alone the cost declines that could make LDES a viable asset class. For example, the Stoney Creek long duration lithium-ion battery is cheaper upfront (on a lifetime- and degradation-normalized basis) than any emerging technology.

Currently, 8-hour systems cost 75% more per kW than 4-hour systems, but are only modestly more valuable. As a result, developers are choosing to build two (ok, 1.75) four-hour systems instead of one eight-hour unit. Same capex, same kWs, different revenues.

Utilities today are choosing to go with short-duration storage now and keep LDES warm for “later.” In fact, most LDES technologies remain stuck at small scale and years behind lithium-ion on cost curves, supply chains, and manufacturing scale. Take Invinity, Eos, and Highview Power as examples. For now, FIDs on commercial projects are the exception, not the rule. Roughly 98% of announced LDES capacity globally still pre-FID.

Because costs are high and demand is low, policy is the only driver of large-scale deployment, with revenue guarantee schemes in the US, UK, and Australia doing some heavy lifting for the industry by giving developers contracted cash flows they can take to lenders on the path to FID. These schemes take several forms, including procurement mandates (Massachusetts Clean Energy Act), cap-and-floor programs (UK and New South Wales, Australia), and centralized procurements (California LLT).

What’s next

- Revenue schemes could drive a few early LDES winners down their cost curves, but vendors who aren’t at demonstration-scale within the next 18 months will miss the first batch of tenders and could fall behind permanently. The dozen or so companies that are mature enough to place serious bids will have to compete with lithium-ion and pumped storage, with no more than a few likely to be successful.

- LDES aspirants have their work cut out for them. If they try to scale quickly by skipping from pilot to commercial, they might find financiers hesitant about tech risk. If they move before building seasoned teams, financing partnerships, and supply chains, risks mount. For utilities, commercialization readiness, not just technology readiness, determines whether they can sign a contract.

- Looking at the multi-day segment, the market is even narrower, limited to regulated utilities who have very strong incentives to maintain reliability Form Energy is the prime example here, having inked contracts with Dominion, Great River Energy, and Xcel Energy. But it has not yet reached FID on a project larger than 1.5MW, with 10MW systems owned by Xcel now at risk after losing grant funding. Regulated utilities may eventually procure multiday storage for reliability needs, but those purchases are the exception for now.

- Utilities are preparing for the future. Their capacity expansion models select four-hour lithium-ion on the basis of cost, while LDES remains a policy-driven add-on. They see a role for eight-hour and multiday systems over time, especially as winter peaks grow and thermal retirements accelerate. But for now, long duration is still too expensive.

At Sightline, we track the industry benchmarks for LDES technologies and startups, as well as their project-level economics and much more, in much greater depth for clients. If you’re interested in accessing the full research suite, talk to our team here.

.svg)

.png)