The state of fusion in 2025: hype, hope, and hard physics

.png)

We all know the joke: fusion is always 30 years away. And the joke still lands in 2025. Despite billions pouring into startups, many are hitting roadblocks. Just last month, General Fusion laid off a quarter of its staff due to financial strain. Project Blixt, once backed by Google, shuttered after its frozen-fiber Z-pinch concept failed to sustain plasma. At the same time, others are pushing milestones. Astral Systems announced at a recent fusion conference that its multi-state reactor successfully bred tritium — the critical fuel for fusion — for the first time.

So, are we really closing in on ignition, or are we still idling? Let’s unpack the state of fusion in 2025: who’s building, who’s bluffing, and what the data shows.

Key takeaways

Fusion continues to outperform most clean energy peers in terms of investment growth, with national competition providing powerful tailwinds. Companies are setting ambitious targets, but the physics is still unproven — and even if devices connect to the grid in the 2030s, that doesn’t mean they’ll be economically competitive.

But fusion isn’t just about 2035 power plants. Near-term opportunities, from medical isotopes to superconductors, are already spinning off tangible value.

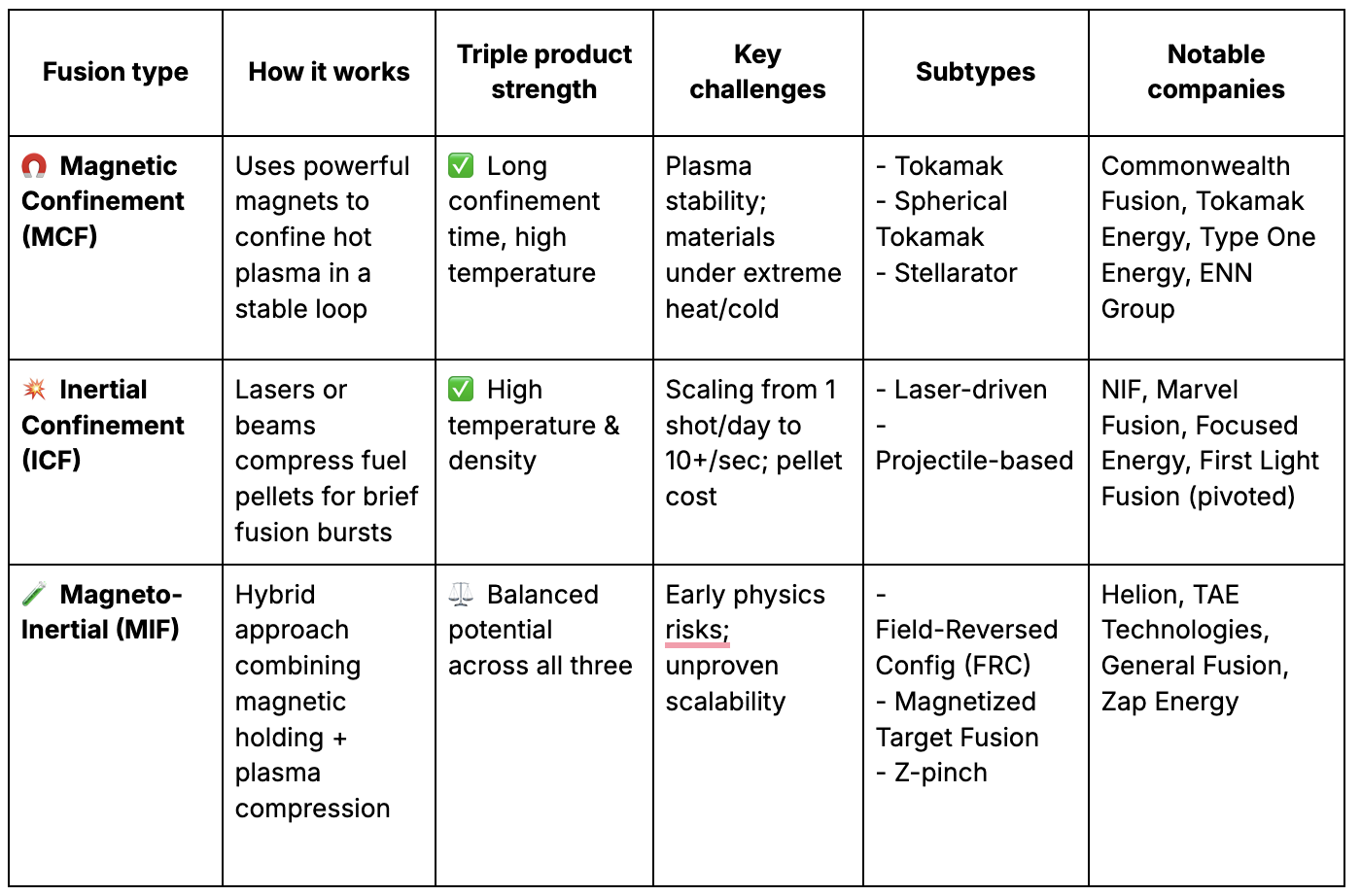

Fusion refresher: one goal, many gambits

Fusion isn’t one technology. It’s a family of competing — sometimes contradictory — approaches all chasing the same goal: a commercially competitive power plant. The first major milestone is achieving Q > 1 (getting more energy out than in), measured through what physicists call the triple product (temperature × density × confinement time).

Here’s a comparison of the leading fusion approaches:

*Only inertial confinement at NIF (Lawrence Livermore) has demonstrated ignition, but commercial viability is far away.

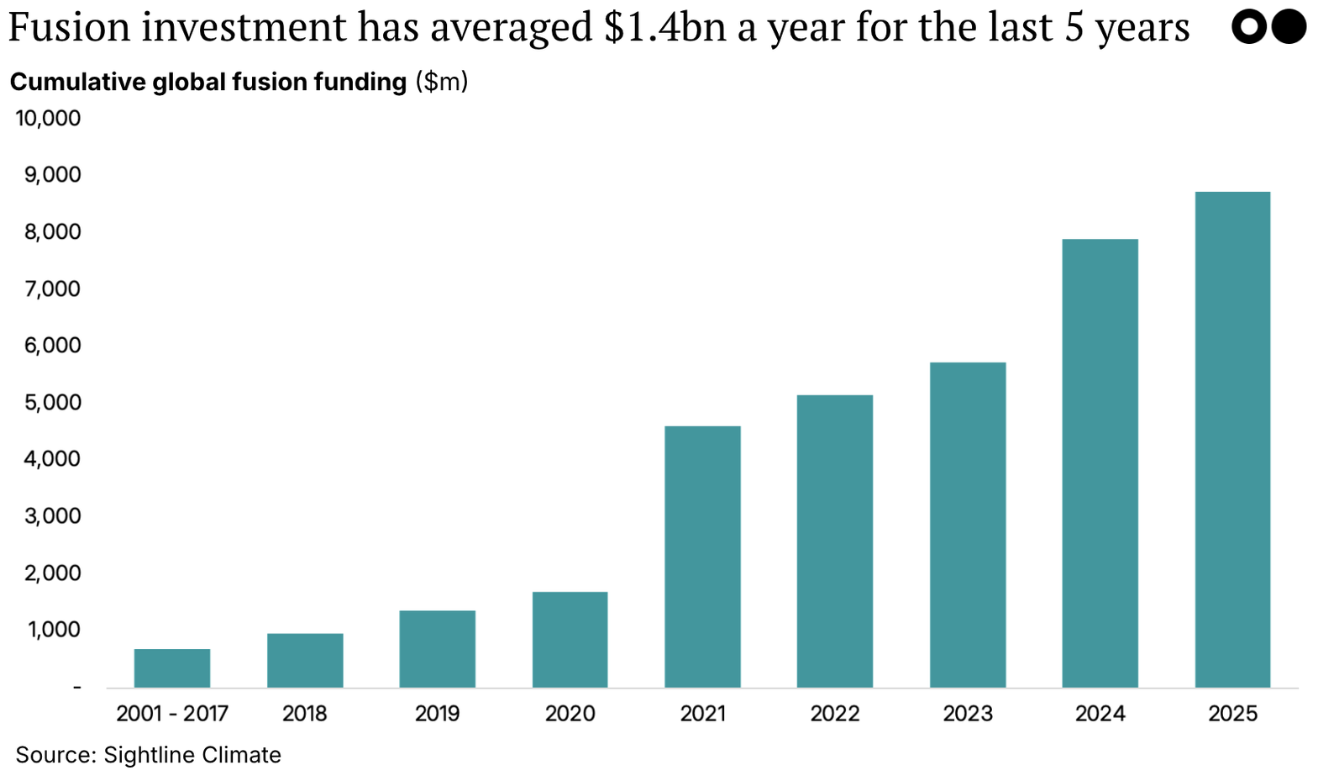

The investment landscape

Fusion is attracting serious capital: more than $9 billion raised globally, with $7 billion in the last five years alone. The majority comes from the US and China, with Europe (UK, France, Germany) and Canada also stepping up.

But most of that is concentrated in mega-rounds: Commonwealth Fusion ($1.8 billion+), China’s NeoFusion ($1.3 billion), Helion Energy ($425 million), and ENN Group’s $400 million internal R&D.

Investors are clustering around tokamaks (the most mature) and FRCs (bets on breakthroughs). Still, funding ≠ readiness. First-of-a-kind plants will cost $1–$5 billion, and real costs may be much higher. No company has yet achieved Q > 1, closed the tritium fuel loop, or proven materials that can survive decades of plasma bombardment.

Fusion geopolitics and policy

Fusion is not only a scientific moonshot, but also a geopolitical asset, a regulatory wildcard, and a deployment challenge all rolled into one.

Regulators are still debating whether fusion should be treated like fission (with stricter nuclear rules) or like particle accelerators (which have a lighter-touch). Developers are lobbying hard for the latter, but harmonization across borders is uncertain.

Meanwhile, the supply chain is already a flashpoint. Lithium-6, essential for breeding tritium, is largely controlled by China. That raises long-term sovereignty risks for Western projects.

China itself is pursuing ambitious strategies, including a fusion–fission hybrid that could burn nuclear waste with fusion neutrons. If successful, it could transform nuclear waste from a liability into a fuel source.

Elsewhere, governments are favoring domestic champions: Tokamak Energy in the UK, Kyoto Fusioneering in Japan, and multiple US firms backed by ARPA-E.

Deployment: between promises and physics

At least ten companies promise to build first-of-a-kind power plants by the early 2030s. But technical blockers remain daunting. None have hit Q > 1, few have closed the fuel cycle, and none have solved materials durability for continuous operation.

Even if fusion plants connect to the grid by 2035, they may suffer low capacity factors, rely on scarce tritium, and run at a loss for years. The gap from plasma experiments to profitable power is wide — and politically entangled.

Can fusion make money before the grid?

Investors aren’t waiting until 2035. Several adjacent markets are already monetizing fusion’s toolset:

- Medical isotopes: Companies like Shine Technologies are producing isotopes for cancer treatment using fusion-based neutron sources.

- High-temperature superconductors (HTS): Advances in magnets are spilling over into grid upgrades, aviation, and space. Tokamak Energy spun out TE Magnets to sell HTS magnet technology.

- Nuclear waste recycling: Fusion neutrons could help reprocess spent nuclear fuel, turning waste into input.

- Advanced materials: Fusion’s extreme environment is driving breakthroughs in shielding, thermal protection, and defense-grade materials.

In short: fusion doesn’t need to wait for FOAK plants to generate value.

Conclusion

Fusion is still a moonshot. The physics is unforgiving, the costs are massive, and timelines are slippery. But the surge in funding, government backing, and technological spillovers means it’s not just hype. Fusion may not light our homes by 2035, but it is already shaping adjacent industries — and could redefine the future of energy in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

👉 Want to dig deeper? Reach out to the Sightline team to explore how fusion fits into your strategy.

.svg)

.png)